Three Implementation Experts Answer Your Questions on COVID-19 and Nutrition Programming

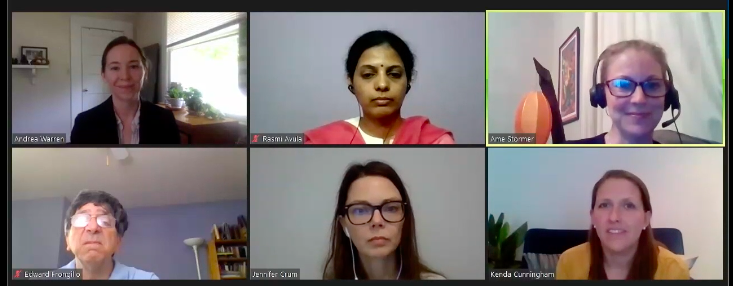

During our Implementation Science workshop co-hosted with ASN as part of their recent Nutrition 2020 Live Online event, Ms. Jennifer Crum (JC) from FHI360, Dr. Rasmi Avula (RA) from IFPRI, and Dr. Ame Stormer (AS) from Helen Keller International, shared their real-world experiences responding to the challenges faced by nutrition programs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The lively discussion that followed their presentations was facilitated by SISN Board Members, Dr. Andrea Warren, Dr. Kenda Cunningham and Dr. Edward Frongillo. A recording of the live stream of the full 90-minute workshop is available here until July 5th, after which date it will be accessible to ASN members only.

This blog highlights the thoughtful questions that were posed by attendees and shares our expert speakers’ insightful responses in text and audio. Due to time limitations, only questions 1-4 were addressed during the live broadcast, but our speakers have graciously agreed to share their responses to the remaining questions below for additional learning.

RA: Our information about how interventions are being implemented currently comes from our partners … [Hear the complete response here]

JC: In our areas we have vitamin A campaigns and immunization campaigns scheduled in the last couple of months and what we have found …. [Hear the complete response here]

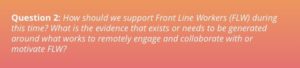

JC: This is one of the biggest challenges that we have and I think globally it is one of the largest challenges for us as nutrition programmers because … [Hear the complete response here]

RA: In India the program in implemented under the National Nutrition Mission, where FLW have received mobile phones, this was pre-COVID … [Hear the complete response here]

AS: I think there is a lot we don’t know, and a lot that we’re learning every day. There is a lot of concern both institutionally but also from our staff about … [Hear the complete response here]

RA: I am not aware of any efforts that are looking at that particular issue but it would be a great thing to see. There are district level data available … [Hear the complete response here]

AS: Our population may be a little bit distinct in that we are covering all poor and extreme poor in the community, which is about 80% of the population … [Hear the complete response here]

JC: Working in a very geographically different area of Bangladesh we will have some of the same issues. We also target the poor and extreme poor … [Hear the complete response here]

RA: When we talk about disparities we need to talk about geographical disparities as well as the wealth disparities … [Hear the complete response here]

JC: When Bangladesh’s lockdown began, we immediately shifted all communication to virtual means. Despite mobile phone communication built into our programming, implementers and beneficiaries found the full shift to virtual communication challenging. FHI 360 and implementing partners drafted telephone talking points for field-level service providers. These conveyed the program’s important nutrition messages in simple, straightforward ways to help service providers develop comfort and confidence with virtual counseling and routine communication.

Outside Bangladesh, FHI 360 has successfully conducted remote in-depth interviews, used research to explore successful data collection methods and authored blog posts to support researchers. These blog posts can be accessed here and here.

Focus group discussions may also be conducted using telephone, Skype, Zoom or a similar technology platform. Researchers must consider responder comfort and connection availability for virtual group sessions. It may be necessary to amend your research protocol and change to individual interviews. Researchers must maintain data quality by ensuring protocol amendments if required, adapting consent processes, assessing the most appropriate virtual interview methods for interviewers and respondents and reviewing incoming data and making real-time adjustments as needed.

AS: Survey data is being collected telephonically during the COVID-19 lockdown. We have household phone numbers for more than half of our participants. We are asking them about food availability and pricing, market opening, transportation availability, household food insecurity, knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 prevention and mitigation measures, and other key information needed to engage in relief and longer term interventions.

RA: The Mid-Day Meals program in India has been suspended due to school closures. In some states, dry rations are being home delivered or being provided through the public distribution system in lieu of the cooked meals. This blog gives more details about the program.

I am not aware of integrating immunization into NSLP. Iron-folic acid supplemental for in-school adolescents is, however, provided through schools.

JC: When shifting from in-person household counseling to telephone communication with beneficiaries, i.e., pregnant women and lactating mothers, we worried that family members would be less involved. Culturally, husbands are unaccustomed to their wives having frequent mobile communication and would intervene during telephone calls. The unintended, but beneficial effect was that husbands became involved in the conversations, so messages could be passed to entire households. This helped build support for women to maintain recommended nutrition practices. In such stressful times, families have reported feeling supported and thankful for the telephone communications, which has helped strengthen trust in the community service providers for future programming.

RA: There are anecdotes from the ground, during the lockdown period, fathers and family members were listening in on or viewing counseling messages along with mothers. However, at this stage, this is still anecdotal information only. We need to build a systematic evidence base to understand to what extent such a positive outcome is prevalent on the ground.

AS: SAPLING has done individual household visits for all pregnant and lactating women and speak with all household members who are present (with staggered visitation to take into account women who are outside of the house during the day) as well as direct group sessions with men, adolescents, and senior women in the community. So all messaging was being triangulated before COVID-19. Going forward however we are taking a more whole of household approach to target women but also their support networks.

JC: It’s important for community workers to promote appropriate practices through all available platforms as part of routine programming. For example, hand-washing and hygiene practices are important for both nutrition and COVID-19. During one-on-one communication, community workers should reinforce the practices they’ve always recommended, and link those to enhanced individual and household protection from COVID-19. Implementers can also use public loudspeaker announcements, billboard placements and local media to spread locally approved, global health messages. Finally, implementers should set good examples by practicing recommended health measures such as wearing a face mask and practicing proper physical distancing.

RA: Behavior change is indeed difficult to achieve and particularly when individuals and communities’ sense of risk perception is low. There are behavior-change models in public health that describe the importance of risk perception to trigger an intent to act. A couple of recent surveys in a few parts of India showed that communities in general are aware of the risk from COVID-19, but their own perception of falling sick due to the virus was low. Depending on the context you are in and the kind of awareness raising campaigns that are in place, perhaps one approach could be to target sub-groups of individuals and raise their own risk perception.

AS: This is certainly true for some of our project areas. We have asked key influencers, village heads, persons of influence to wear a mask and ensure that they are following restrictions i.e. 2 meters of distance, no spitting. We also have Red Crescent Youth walking through villages while masked and with bullhorns to talk about prevention messaging which has been a low-tech information mechanism people seem to like.

JC: The implementation research agenda employs a variety of methods to gather robust information on program effectiveness, fidelity, feasibility, acceptability, adoption and reach. The study utilizes baseline and end-line surveys to assess effectiveness and cost data to perform program cost and cost-effectiveness analyses. In-depth interviews and focus group discussions collect qualitative information from service providers, participants and participants’ husbands. Program monitoring and evaluation data is strategically mined to complete a process evaluation. Finally, critical to implementation research is the uptake of evidence. For this component, the program works to build nutrition stakeholders’ capacity to utilize evidence produced and strengthen the Bangladesh ecosystem for evidence utilization.

AS: We have several different research activities planned, to look at resilience of market systems and develop a validated measure of self-efficacy which we think is a key factor in women’s empowerment. Both of these studied call for mixed method analysis- both are on hold during the lockdown. We are hoping to move forward with in person interviewing, at least for the qualitative pieces of this- but will have to adhere to COVID-19 prevention methods, including distancing, masking and not sharing snacks which is a commonly used incentive in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

RA: Building on our frontline worker portfolio of work, we are embarking on a study to understand the changes to delivery modalities of existing maternal and child health and nutrition services in the current COVID-19 scenario. We are curious to know FLWs adaptations, challenges, and motivations in delivering services in the new “normal”. To generate comparable learnings from multiple geographies, and build a compendium of research, we are also bringing together partners interested in the topic and developing a collaborative approach. The intent is to work together and use a common survey instrument and conduct phone surveys leveraging on existing research networks to collect the data.

Let’s keep this conversation going. If you have any thoughts or comments on this discussion, we’d like to hear from you! Please send any feedback to: info@implementnutrition.com